Top Security News

An 'electronic island': How Indian EVMs are different | India News - Times of India

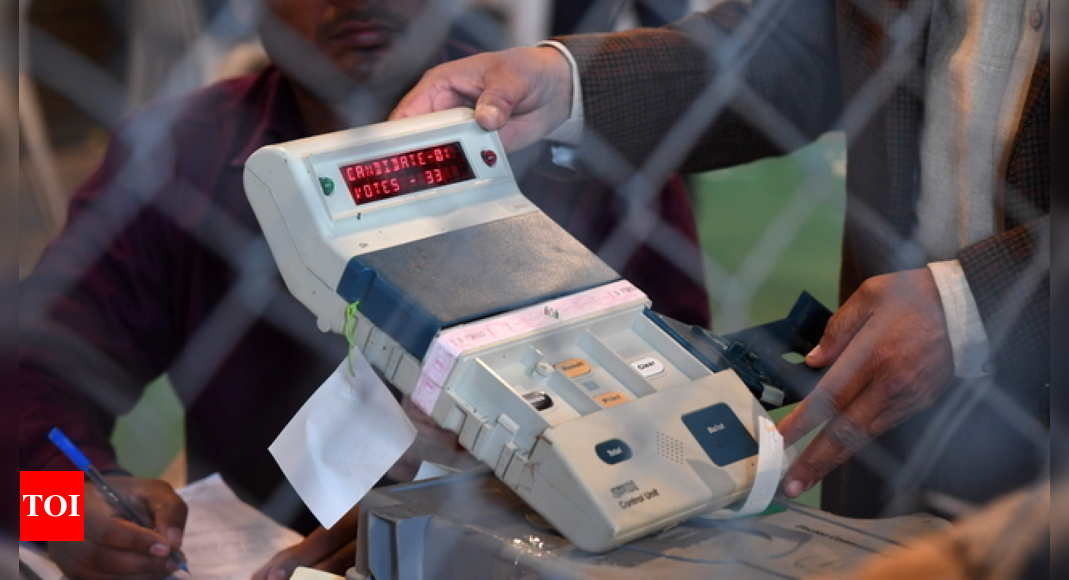

Indian EVMs are complex machines that are built to be tamper-proof, say engineers and domain experts. In fact, they pointed to added features in the M3 (model 3) EVM - more than 600 million people cast their votes on it in the recent Lok Sabha polls - that double down on its security aspects.

Rajat Moona, director, IIT Gandhinagar and a member of the technical panel responsible for designing EVMs, likened the device to a simple calculator and maintained that "no EVM can be hacked into or tampered with".While the debate is political in nature, he said, technically, the "Indian EVMs cannot be hacked".

Built on best practices

The M3 model is smarter than its predecessor and has several functions that are automated, including a first-level check like what computers carry out before they boot up. "The EVMs, if tampered with, also have a technology to return to factory setting and stop responding completely," explained experts. These machines are not connected to the internet nor do they have an RF (radio frequency) to respond to Bluetooth. In fact, they are not even connected to a power socket.

Introduced in 2019, M3 machines will be used for several state polls and have a lifetime of 15 years before they are phased out and an updated version is launched. "We are already exploring all the new technology that can be brought in for the M4 machines," said a member of the expert panel.

So, why the doubts?

Weeks after the 2024 LS polls, tech billionaire Elon Musk called for the junking of EVMs, saying "the risk of being hacked by humans or AI, while small, is still too high". Musk's post on X -- which former Union MoS IT Rajeev Chandrasekhar described as a "huge sweeping generalisation" - was in response to a post on EVMs in Puerto Rico.

But Moona sees the current conversation around ways to gain illegal access to EVMs as being political in nature and said he'd therefore like to steer clear of it. Interestingly, to "remain completely independent", none of the EVM technical panel members either charge fees or accept any honorarium for designing the architecture or technology of the voting machines.

According to Dinesh Sharma, emeritus professor and expert in microelectronics and solid-state electronics at the department of electrical engineering of the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, "that was the only way we knew we could remain totally and completely independent".

'Can't do anything else'

After every election, there are "canards" made against Indian EVMs and how they can be hacked. To clear the air and bust the myths, Sharma has put up a two-hour-long talk in the public domain. He also plans to release an updated video in about a month on the new machines and the security features in them to allay the fears of the general public.

In his video, Sharma distinguishes between voting machines in other parts of the world and the ones used in India. "Indian EVMs are different from other EVMs in the world. The M3 EVMs have no connection to any other device, not even main power supply. EVMs do not talk to any other device. They are only designed for voting and are not a general-purpose computing device with a loaded programme for electronic voting. So, our EVM can do nothing else. No other programme or software can be loaded on to them."

Sharma adds that in case of any issue with an EVM, the machine has to be discarded altogether. "Each EVM is a unique electronic island in itself, and this makes them super secure," he says.

Multiple checks and constant vigil

At every step, EVMs undergo third-party review of software while mock polling is done multiple times in the presence of candidates' representatives. After these checks, the machines are sealed with "rare" paper from the Nashik security printing press, the same paper used to print Indian currency notes. Each time the machines are sealed or opened, it is done in the presence of election candidates or their representatives.

Also, when EVMs are transported and stored before polling day, the storage room has to meet strict criteria, like having only one door. "There is also a provision to allow candidates or their representatives to camp outside 24/7 till the polling day," explains Sharma.

Mismatch due to 'Human Error'

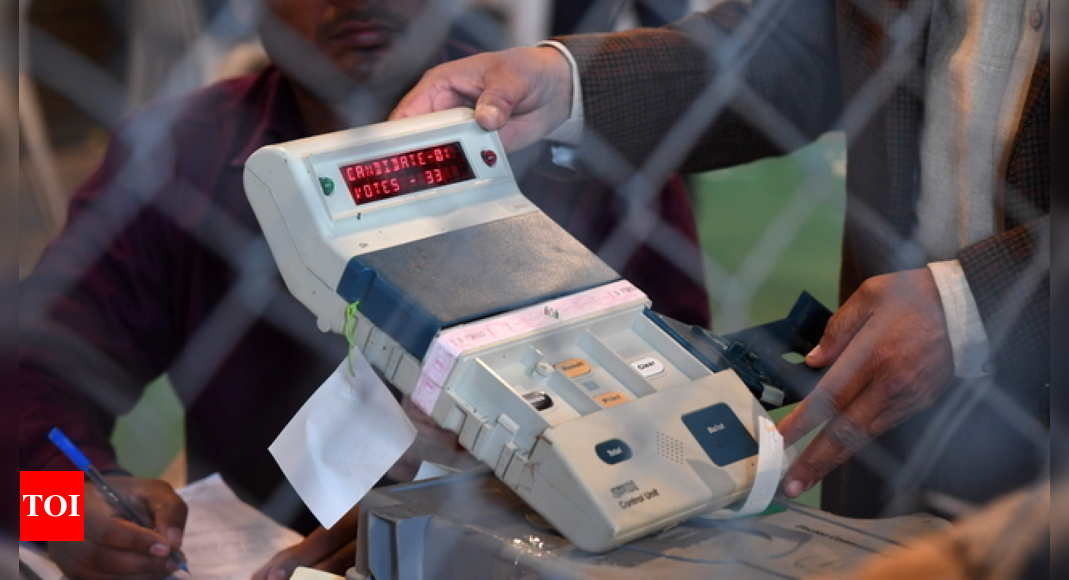

Following a Supreme Court order, tallying of ballot-slip counts of 20,625 randomly chosen VVPATs is carried out with the electronic counts of their control units for the general elections.

If no mismatch between EVM and VVPAT counts is found in such a sample, then it can be said with near certainty that the sanctity of the election process is not disturbed by the use of EVMs, experts said. Till date, ballot slips of 41,629 randomly selected VVPATs have been tallied with the electronic counts of their control units and not a single case of transfer of vote meant for candidate 'A' to candidate 'B' has been detected.

Differences in count, if any, have always been traceable to human error, like non-deletion of mock poll votes from the control unit or non-removal of mock poll slips from the VVPAT.

0 Comments

Post a Comment

Scroll to Top